| : A Day at Everest Base Camp |

by David Ford

Sunday, 29 April 2001

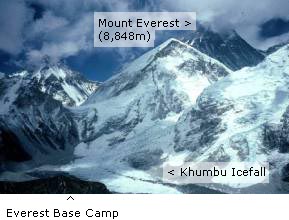

Just after 7am on a clear, sunny morning at the Snowland Lodge in Gorak

Shep (5,170m). Small groups of brightly dressed trekkers are eating breakfast

in the common room, getting ready for their day. Some will be climbing nearby

Kala Patthar (5,554m) for a view of Everest Base Camp and Mount Everest before

the late morning clouds roll in. Others will be hiking up to Everest Base

Camp itself, or back down the valley to Lobuche (4,950m) on their way out

of the Solo Khumbu region.

Just after 7am on a clear, sunny morning at the Snowland Lodge in Gorak

Shep (5,170m). Small groups of brightly dressed trekkers are eating breakfast

in the common room, getting ready for their day. Some will be climbing nearby

Kala Patthar (5,554m) for a view of Everest Base Camp and Mount Everest before

the late morning clouds roll in. Others will be hiking up to Everest Base

Camp itself, or back down the valley to Lobuche (4,950m) on their way out

of the Solo Khumbu region.

The sound of a helicopter’s blades grows louder as it flies into our narrow valley, following the lower stretches of the Khumbu Glacier. Last night’s radio news had been sobering. Babu, a highly respected Sherpa sirdar, was walking near Camp #2 on the upper portion of the Khumbu Glacier and had fallen to his death in a hidden crevass. Babu was a family man, with a wife and six daughters, and had personally summitted Everest on several occasions. Traditionally, the Sherpa people have an adversion to a human corpse. However, the expedition had insisted that this body be carried down through the treacherous Khumbu Icefall to Everest Base Camp, where it could be picked up and flown out for burial.

As the helicopter engine fades up-valley towards Base Camp, Sherpa guides and kitchen staff make their way outside, and line up on the moraine ridge overlooking the glacier. Minutes later, the helicopter can be heard lifting off from Base Camp, and we stand and watch as it flies by, heading back towards the town of Namche Bazar. Just another reminder that the Himalayas continue to exact their toll from expert and novice alike; you can never take life for granted in Solo Khumbu.

Although the dangers of trekking and climbing will remain, technology has changed the tourist industry in Nepal. Every major lodge now has a satellite phone, which they use to take bookings of incoming trekking groups. Before heading out this morning, I make a one minute call back to Brandon and leave a message on my answering machine at home.

We are going to return to the Snowland Lodge this evening, and so today’s walk will only require a small belly pack to carry the drinking water and lunch. Since leaving the airport at Lukla nearly thirteen days ago, it had become obvious thatI had been carrying too much junk in my 65L backpack. Last night I donated 2kg of gear to the lodge’s manager.

Our small trekking threesome includes my

younger brother, Barry, and his wife Joanne. We pull out of Gorak Shep just

before 8am. To the northwest, a trickle of day trippers are making their

way up the black rocks of Kala Patthar (5,554m) for a view of Everest Base

Camp. The icecapped summit of Pumo Ri (7,165m) dominates the northern skyline,

and the previous evening’s skiff of snow is melting in the morning sunshine.

The trail is well defined and easy to follow as it veers off northeast. After

all, there is only one final destination for those who have climbed this high

and come this close to these mountains along the Tibetan border. Very shortly,

the trail heads out from behind the lateral moraine and winds over the Khumbu

Glacier, a rolling and broken mass of grey rocks and rubble, completely covering

the ice beneath. There is no need to rush. The terrain is difficult and there is a risk of a twisted

ankle.

Our small trekking threesome includes my

younger brother, Barry, and his wife Joanne. We pull out of Gorak Shep just

before 8am. To the northwest, a trickle of day trippers are making their

way up the black rocks of Kala Patthar (5,554m) for a view of Everest Base

Camp. The icecapped summit of Pumo Ri (7,165m) dominates the northern skyline,

and the previous evening’s skiff of snow is melting in the morning sunshine.

The trail is well defined and easy to follow as it veers off northeast. After

all, there is only one final destination for those who have climbed this high

and come this close to these mountains along the Tibetan border. Very shortly,

the trail heads out from behind the lateral moraine and winds over the Khumbu

Glacier, a rolling and broken mass of grey rocks and rubble, completely covering

the ice beneath. There is no need to rush. The terrain is difficult and there is a risk of a twisted

ankle.

Two hours later we reach the outskirts of

the tent city, popularly known as Everest Base Camp (5,363m). This year there

are thirteen expeditions encamped on the glacier -- 400 colourful tents scattered

among the boulders and ice, supporting a population of nearly 2,000 people.

Twice every year (during the climbing seasons of April/May and September/October)

this becomes the largest town in the Solo Khumbu region. The seemingly insatiable

demand for food and supplies is supported by a stream of yak caravans and

human porters that turn our narrow trail into a veritable highway.

Two hours later we reach the outskirts of

the tent city, popularly known as Everest Base Camp (5,363m). This year there

are thirteen expeditions encamped on the glacier -- 400 colourful tents scattered

among the boulders and ice, supporting a population of nearly 2,000 people.

Twice every year (during the climbing seasons of April/May and September/October)

this becomes the largest town in the Solo Khumbu region. The seemingly insatiable

demand for food and supplies is supported by a stream of yak caravans and

human porters that turn our narrow trail into a veritable highway.

Each climbing expedition can be identified by its Buddhist prayer pole and the long radiating lines of red, yellow, blue, and green prayer flags whose ends are anchored with piles of broken rock. There is no real plan or design for a camp. Rather, the expedition tents are scattered amongst the nearby rocks and ice wherever there is a flat enough spot. The brightly coloured four-person tents hold either climbers or base camp staff. The larger blue or black tents are used for storage and cooking. Off to the side are a couple of ubiquitous small brown toilet tents.

The trail has virtually disintegrated in

the mess of tents, and so we follow three climbers who are heading eastwards

through the camp, towards the looming Khumbu Icefall. A large crest on the

back of their jackets announces them as the “Russian Lhotse Expedition 2001”. Away from the rocks and rubble, we clamber over increasingly

bare ice, then come around a jagged outcropping of ice to reach the toe of

the Icefall. A hemp rope hangs from the steeply sloping ice face, crampon

tracks alongside and underneath it.

The trail has virtually disintegrated in

the mess of tents, and so we follow three climbers who are heading eastwards

through the camp, towards the looming Khumbu Icefall. A large crest on the

back of their jackets announces them as the “Russian Lhotse Expedition 2001”. Away from the rocks and rubble, we clamber over increasingly

bare ice, then come around a jagged outcropping of ice to reach the toe of

the Icefall. A hemp rope hangs from the steeply sloping ice face, crampon

tracks alongside and underneath it.

The three Russian climbers throw down their packs and begin attaching climbing crampons to their boots, animatedly talking, ignoring the three mere trekkers. One by one the Russians grab the rope and pull themselves over the first ice ridge, disappearing and then reappearing in the successive folds of ice and snow that climb over 1,000m toward the upper Khumbu Glacier. Individuals and small groups of other climbers can be seen high above them, black dots against the white and blue. They are ascending or descending the icefall before the warming sun makes it a more dangerous route.

In theory, there is a US$10,000 fine for going past this point without the proper permits. However, two young Dutch trekkers show up and use the rope to haul themselves up the same ice ridge, posing for pictures at the top, then disappearing over the far side. Our group of three finds a flat piece of rock and enjoys a cold lunch of boiled eggs, cookies, and chocolate bars.

Barry and Joanne head straight back to Gorak

Shep, but I have

heard that some of the expeditions actually welcome visits from trekkers.

A group of white canvas tents looks interesting, and so I walk over and introduce

myself to several members of the Indian Army Expedition. Their camp faces

the icefall with Lhotse and the Lhotse Face at the top. What a view to wake

up to each morning! A couple of them invite me to sit down, drink some pineapple

juice, and chat. It turns out that their climbing group is “All up” and the biggest job for them right now is

how to deal with the boredom. I met the major in charge of base camp, was

introduced to the team doctor, and signed the guest book. After half an hour,

I reluctantly say my goodbyes and journey on through the mass of tents.

Barry and Joanne head straight back to Gorak

Shep, but I have

heard that some of the expeditions actually welcome visits from trekkers.

A group of white canvas tents looks interesting, and so I walk over and introduce

myself to several members of the Indian Army Expedition. Their camp faces

the icefall with Lhotse and the Lhotse Face at the top. What a view to wake

up to each morning! A couple of them invite me to sit down, drink some pineapple

juice, and chat. It turns out that their climbing group is “All up” and the biggest job for them right now is

how to deal with the boredom. I met the major in charge of base camp, was

introduced to the team doctor, and signed the guest book. After half an hour,

I reluctantly say my goodbyes and journey on through the mass of tents.

A film crew is taping a segment for “Good Morning America” with an anti-drug theme. Something about how the actor could not have made it all the way to Everest Base Camp if he were taking recreational drugs. I watch as they re-shoot the lines several times. Finally they get it right, upload the tape and send it to New York via satellite.

At 12:35pm, the clouds begin to roll in. It is time to head back to the lodge. Lots of traffic on the trail, heading in both directions; late risers just making it into Base Camp, others making the slow walk back to Gorak Shep. The high altitude affects everyone differently. Some trekkers get very short of energy. Others notice nothing at all. Just before Gorak Shep, I catch up to Barry and Joanne. They are poking along, taking it easy. So, I go on ahead to the Lodge and order a hot drink to be ready for their arrival.

Throughout the afternoon, the lodge’s dining room fills up as residents return from Base Camp and new trekkers arrive

from below. A group of twenty trekkers from South Africa has hiked up from

Lobuche, the previous town on the main trail. The lodge is now packed to the

rafters. Every room is full, and the dorms are overflowing. We talk, we laugh.

Card games are being played around the room. When the sun sets, someone lights

the pot-bellied stove and piles in the yak dung for more heat. The South

Africans eat first. Tour groups have priority. Finally, at 8pm, the manager

flashes the solar battery operated fluorescent lights. We must vacate the

common room because the  porters sleep on the benches and they want

to go to bed.

porters sleep on the benches and they want

to go to bed.